The Goshawk, Accipiter gentilis, (Accipiter being Latin for ‘hawk’, which comes from accipere, ‘to grasp’, and gentilis meaning ‘noble’,) known as the ‘Queen of the Forest’, is quite a large raptor, with the adult standing up to 70cm tall and having a wingspan of around 1 metre. As with other raptors, like the Peregrine and Sparrowhawk for example, there is a pronounced size difference between the sexes, though in this case roles are reversed with the male being larger than the female, rather than smaller as with most other raptors.

They are known as the ‘Queen of the Forest’, for two reasons, one being that they prefer thickly wooded parts of the countryside to hunt and nest, building large nests out of sticks in the darkest, most secluded corners, which they will defend fiercely if discovered. Although they can hardly be called timid, they are very elusive and rarely seen, keeping to their shadowy realm for most of the time where they glide and hunt between the branches and tree trunks.

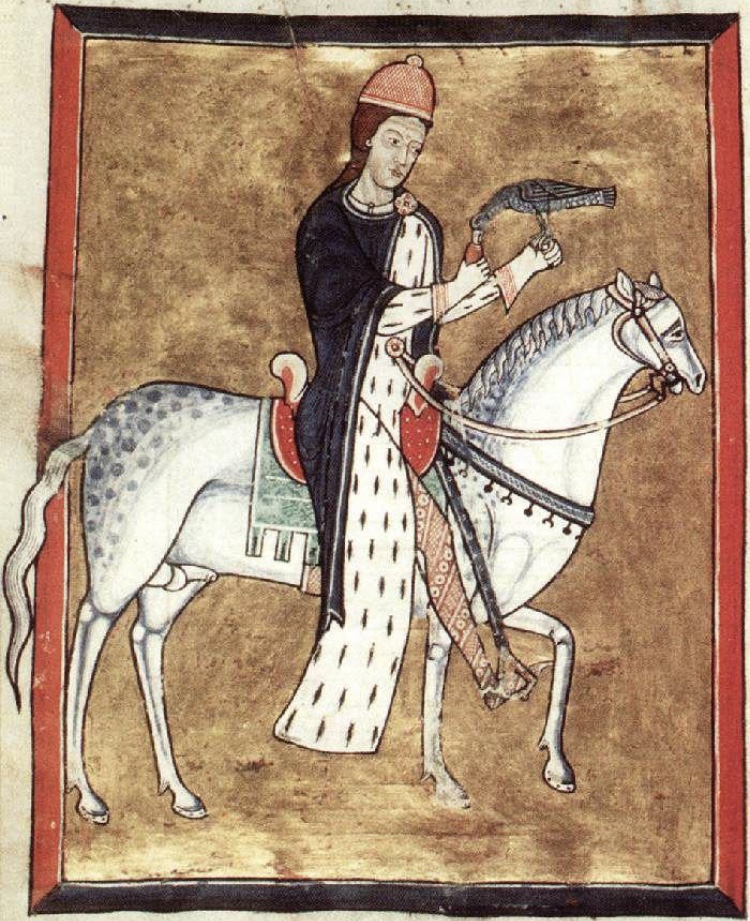

The other reason for their name is that in medieval times they were considered the hawk of choice for nobility to take along when hunting game in the country’s ‘Silva regis’ or royal hunting forests, as their versatile nature and ability to bring down most game meant that were of more use than other, more refined, hawks, especially when the terrain and conditions might be unknown.

Over the centuries this meant that the Goshawk became synonymous with royal forests and it has been adopted as an emblem for many areas with this background, such as the Forest of Bowland in the North of England, where its proud likeness, complete with barred tail and hooked beak, grace some of the older signs which greet you when entering the region.

In recent years some of the signs have been altered, without consulting residents of the area, by groups such as raptor-politics, they were repainted in the likeness of the Hen Harrier, which was very common in medieval times and considered a pest, (hence the name ‘Hen Harrier’) rarely, if ever, flown by falconers and certainly not known as a noble bird symbolic of the Silva regis.

Steel-blue with red eyes

Adult Goshawks wear steel-blue/grey plumage over their streamlined bodies with a paler breast and underneath which bears a pattern consisting of strongly defined bars, they are also bestowed with a distinctive scowl, given them by their white eyebrows, called ‘supercilium’, and piercing red/orange eyes. The juvenile is browner in colour and has vertical streaking on its chest, rather than bars, which develop later.

In appearance they are most similar to the Sparrowhawk, with both having grey/blue plumage and prominent barring on their tails, although the Goshawk is significantly larger than the Sparrowhawk and can also be distinguished by the red eyes, as opposed to the Sparrowhawk’s more typical yellow, the white supercilium, and by having a thicker base to the tail, which quite often has bright tufts of white feathers around it too.

Sky Dancing

Around late winter to early spring both the Sparrowhawk and Goshawk carry out similar displays over their potential breeding territories, these consisting of flights by both the male and female in which they both fly with slow, exaggerated wingbeats which lead up to the famous ‘sky-dance’.

With Goshawks it is the female who takes the lead, and the spectacular culmination of the display is a series of dives, or ‘switch-backs’, starting with a sudden, nail-bitingly, terrifyingly fast dive, which looks like it might end in disaster. Instead the hen Goshawk pulls a show-stopping recovery at the very last moment, followed by lightning-fast upwards climb, wings held tightly to her sides, after which she trims out and resumes her slow and languid circuit which she was doing prior to pretending to be a Kamikaze pilot.

They will repeat this ‘sky dancing’ display several times over the course of the whole show and the dives seem to get more and more reckless, until you almost expect to hear a sonic boom!

Powerful Predators

Goshawks are naturally fast and powerful flyers but in a normal day as they go about their business they fly with slow and deliberate wingbeats, in which the wings are clearly and evenly flapped both above and below the horizontal, these are occasionally interspersed with periods of flight where they fly with rather desultory looking flaps from the horizontal downwards, in the same way that a Cuckoo will fly from one point to another.

This is usually when they are less determined about where they are going, and sometimes they will simply hang in the air for long periods, gliding and barely flapping their wings at all, whilst they observe the ground and trees below, spying any movement which might signify prey.

When they do spot something they want the sudden change in pace is frightening to observe, they will instantly fix on the target they have selected and nothing will deter them from getting at it. Not only are they fast, they are enormously agile too, capable of bringing down prey much larger than themselves and will take a wide variety of prey, with anything from the size of a Squirrel, Woodpigeon or Rabbit, up to animals the size of Hares, Mallard, small Geese and even birds as large and formidable as Herons being taken.

With their strong feet and razor-sharp talons they are able to grip and dispatch any prey very proficiently and have been observed to take out and kill other birds of prey too, in some areas a pair will become the only birds of prey present, after they’ve harassed and chased off all rivals.

The Cook’s bird

The Goshawk is as popular amongst falconers now as it is always has been, if not more so, and is still mostly flown after live game. In fact, in the medieval period when falconry was very much just an aristocratic pastime, the Goshawk was commonly referred to as ‘the Cook’s Bird’, as it was so proficient at putting game on the kitchen table.

This connection between human and Goshawk goes back in history a lot, lot further though, with archaeological excavations such as those from the cemetery of Quedlinburg Bockshornschanze in Germany revealing the skeleton of a Goshawk, along with the skeletons of two dogs. These were part of grave goods, buried alongside people of nobility to take with them to the afterlife, and in this case dated to the late 5th or early 6th centuries.

The noble in question there was an Englishwoman and in a similar grave at Eschwege Niederhone, near Hessen, the skeleton of a female Goshawk, together with the skeleton of a dog, was excavated in a large chamber grave from the early 7th century, which was dug for an unknown man.

Austringers

In the ‘Boke of St Alban’s’, which was a compilation of matters relating to the interests of gentleman, such as hunting, and printed in 1486, one of the authors; Dame Juliana Berners, wrote about the various species of hawks and falcons and how they corresponded to ones ranking in mediaeval society;

“And yit ther be moo kyndis of hawkes/Ther is a Goshawke and that hauke is for the yeman/Ther is the Tercell and that is for the powere man/Ther is a Spare hawke and he is a hawke for a prest/Ther is a Muskyte and he is for an holiwater clerke”

This seems to have placed the Goshawk along the ranking of Yeoman, and indeed they are hardly the most refined of hawk, yet irrespective of mediaeval attitudes to both the Goshawk and its attendant Austringer (one who cared for, trained and hunted a goshawk), almost every mews, (the historic name for a building used to keep falcons), had at least one or two, simply because they brought home the most game for the house!

Nowadays numbers of Goshawk are on the increase in the British isles, mainly due to an increase in prey such as Woodpigeon and Grey Squirrels (I know this is a red in this video!), and with the many rewilding and native tree planting schemes being carried out at the moment they will find more suitable habitats in which to hunt in the future.

Hopefully this won’t affect other birds of prey such as the Hen Harrier which, being vulnerable to predation from larger birds of prey and preferring wide open moorland to hunt in, rather than dense woodland, will have to adapt.

A B-H